6.1 Atmosphere

The atmosphere is a blanket of air made up of a mixture of gases that surrounds the Earth. This mixture is in constant motion. If the atmosphere were visible, it might look like an ocean with swirls and eddies, rising and falling air, and waves that travel for great distances.

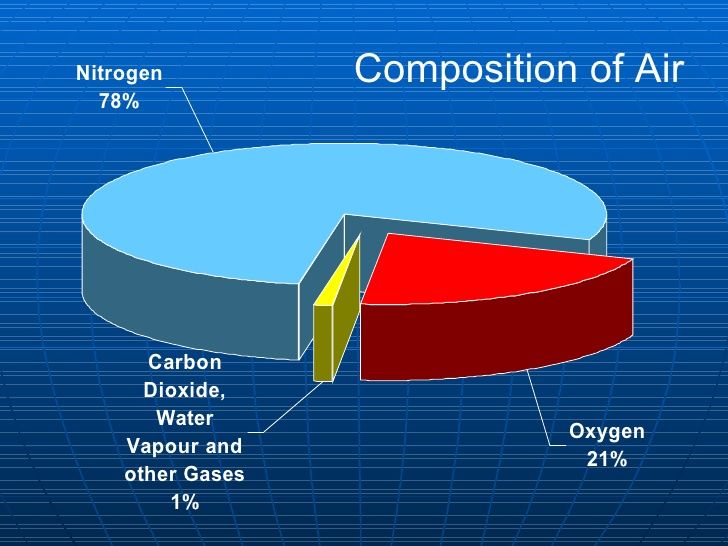

In any given volume of air, nitrogen accounts for 78% of the gases that comprise the atmosphere, while oxygen makes up 21%. Argon, Carbon dioxide, and traces of other gases make up the remaining 1%. This volume of air also contains some water vapor, varying from 0% to about 5% by volume. This small amount of water vapor is responsible for major changes in the weather.

Figure 6.1: Composition of Air

6.1.1 Atmosphere Layers

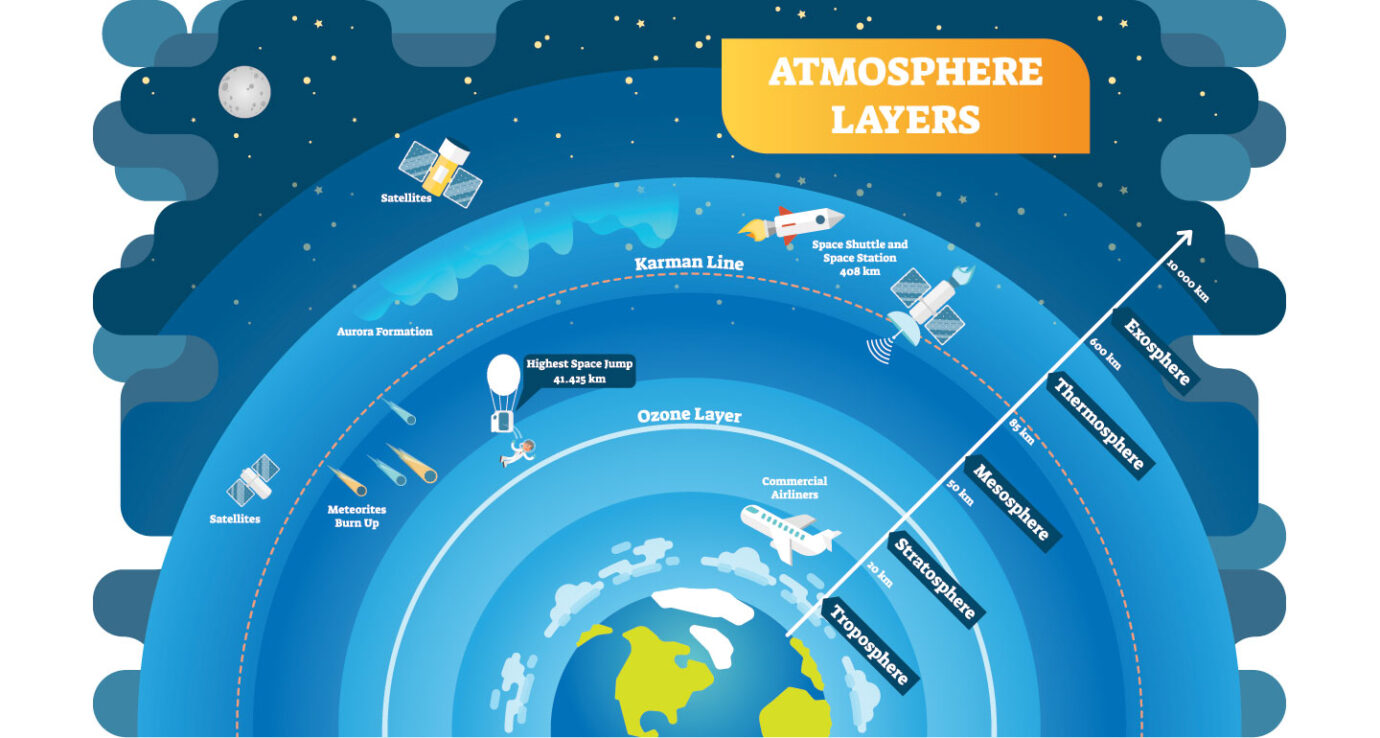

The envelope of gases surrounding the Earth changes from the ground up. Five distinct layers or spheres of the atmosphere have been identified using thermal characteristics (temperature changes), chemical composition, movement, and density.

The first layer, known as the troposphere, extends from 6 to 20 kilometers,km, (19000ft to 65000ft) over the northern and southern poles and up to 14.5km (48,000 feet) over the equatorial regions. The vast majority of weather, clouds, storms, and temperature variances occur within this first layer of the atmosphere.

At the top of the troposphere is a boundary known as the tropopause, which traps moisture and the associated weather in the troposphere. The altitude of the tropopause varies with latitude and with the season of the year; therefore, it takes on an elliptical shape as opposed to round.

Above the tropopause are three more atmospheric levels. The first is the stratosphere, little weather exists in this layer and the air remains stable, although certain types of clouds occasionally extend in it. Above the stratosphere are the mesosphere, thermosphere and exosphere which have little influence over weather.

Commercial airliners usually fly in the tropopause because it offers fuel efficiency, smoother flights, and optimal engine performance. The thin air reduces drag, while stable atmospheric conditions minimize turbulence. Additionally, flying at this altitude helps avoid most weather disturbances that occur in the lower troposphere.

Figure 6.2: 5 Layers of the Atmosphere

6.1.2 Atmospheric Circulation

As noted earlier, the atmosphere is in constant motion. Certain factors combine to set the atmosphere in motion, but a major factor is the uneven heating of the Earth’s surface. This heating upsets the equilibrium of the atmosphere, creating changes in air movement and atmospheric pressure. The movement of air around the surface of the Earth is called atmospheric circulation.

Heating of the Earth’s surface is accomplished by several processes, but in the simple convection-only model used for this discussion, the Earth is warmed by energy radiating from the sun. The process causes a circular motion that results when warm air rises and is replaced by cooler air.

Warm air rises because heat causes air molecules to spread apart. As the air expands, it becomes less dense and lighter than the surrounding air. As air cools, the molecules pack together more closely, becoming denser and heavier than warm air. As a result, cool, heavy air tends to sink and replace warmer, rising air.

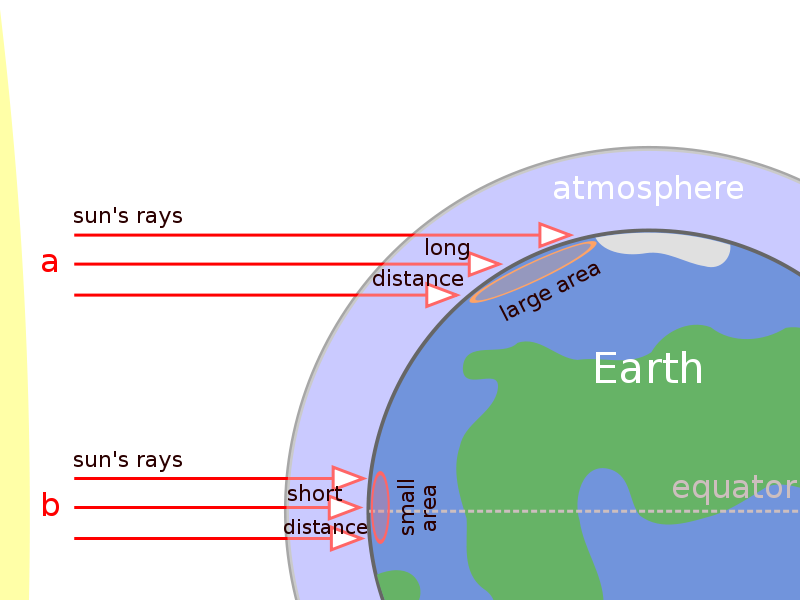

Figure 6.3: Different Surface Areas of Heating

Because the Earth has a curved surface that rotates on a tilted axis while orbiting the sun, the equatorial regions of the Earth receive a greater amount of heat from the sun than the polar regions. The amount of solar energy that heats the Earth depends on the time of year and the latitude of the specific region. All of these factors affect the length of time and the angle at which sunlight strikes the surface.

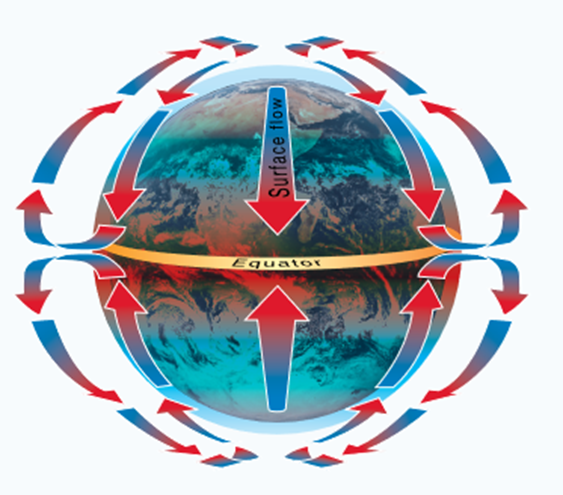

Solar heating causes higher temperatures in equatorial areas, which causes the air to be less dense and rise. As the warm air flows toward the poles, it cools, becoming denser and sinks back toward the surface.

Figure 6.4: Air flow around Polar and Equatorial Regions

6.1.3 Atmospheric Pressure

The unequal heating of the Earth’s surface not only modifies air density and creates circulation patterns; it also causes changes in air pressure or the force exerted by the weight of air molecules. Although air molecules are invisible, they still have weight and take up space.

The actual pressure at a given place and time differs with altitude, temperature, and density of the air. These conditions also affect aircraft performance, especially with regard to takeoff, rate of climb, and landings.

Relationship of Altitude and Atmospheric Pressure

As altitude increases, atmospheric pressure decreases. On average, with every 1,000 feet of increase in altitude, the atmospheric pressure decreases 1 "Hg. As pressure decreases, the air becomes less dense or thinner. This is the equivalent of being at a higher altitude and is referred to as density altitude. As pressure decreases, density altitude increases and has a pronounced effect on aircraft performance. (will be discussed in more detail in.

6.1.4 Coriolis Force

In general, atmospheric circulation theory, areas of low pressure exist over the equatorial regions and areas of high pressure exist over the polar regions due to a difference in temperature. The resulting low pressure allows the high- pressure air at the poles to flow along the planet’s surface toward the equator. While this pattern of air circulation is correct in theory, the circulation of air is modified by several forces, the most important of which is the rotation of the Earth.

The force created by the rotation of the Earth is known as the Coriolis force. This force is not perceptible to humans as they walk around because humans move slowly and travel relatively short distances compared to the size and rotation rate of the Earth. However, the Coriolis force significantly affects motion over large distances, such as an air mass or body of water.

The Coriolis force deflects air to the right in the Northern Hemisphere, causing it to follow a curved path instead of a straight line. The amount of deflection differs depending on the latitude. It is greatest at the poles and diminishes to zero at the equator. The magnitude of Coriolis force also differs with the speed of the moving body—the greater the speed, the greater the deviation. In the Northern Hemisphere, the rotation of the Earth deflects moving air to the right and changes the general circulation pattern of the air.

The Coriolis force causes the general flow to break up into three distinct cells in each hemisphere. In the Northern Hemisphere, the warm air at the equator rises upward from the surface, travels northward, and is deflected eastward by the rotation of the Earth. By the time it has traveled one-third of the distance from the equator to the North Pole, it is no longer moving northward, but eastward. This air cools and sinks in a belt-like area at about 30° latitude, creating an area of high pressure as it sinks toward the surface. Then, it flows southward along the surface back toward the equator. Coriolis force bends the flow to the right, thus creating the northeasterly trade winds that prevail from 30° latitude to the equator. Similar forces create circulation cells that encircle the Earth between 30° and 60° latitude and between 60° and the poles.

Figure 6.5: Illustration of the Coriolis Force

Circulation patterns are further complicated by seasonal changes, differences between the surfaces of continents and oceans, and other factors such as frictional forces caused by the topography of the Earth’s surface that modify the movement of the air in the atmosphere. (will be discussed later )